In December 2022 I completed a course with the University of Guelph on naturalizing and restoring landscapes. My final project was a proposal to create a naturalized garden at Lucas House, in Haliburton, Ontario.

Introduction

Lucas House is a Century home in the centre of Haliburton, Ontario. It is co-owned by myself and is currently home to offices, an art gallery and an artist’s studio. It is surrounded by lawn and has a large gravel parking lot. With its central location, next to the post office, it is an excellent site for a demonstration naturalized garden. Because I co-own the building, I have full control over the project, subject to local bylaws.

There are three main goals for this project:

- Increase biodiversity at the site;

- Solve drainage and shade issues;

- Become a demonstration garden to show the benefits of a naturalized landscape.

Motivations

Human civilization has modified more than 50% of the world’s terrestrial land cover (McGill et al., 2015), released enough CO2 through the burning of fossil fuels that a doubling of the atmospheric concentration is likely in the lifetime of some people alive today (McGill et al., 2015), and hunted and fished to such a degree that dominant top predators are absent or endangered on land and sea (McGill et al., 2015). For these and other reasons, geologists have determined we are now in the Anthropocene – a new geological epoch that recognizes the significant impact humans have had on Earth’s biogeochemical cycles, biodiversity, and ecosystems (Meineke et al. 2019).

Human influence extends to our urban environments, including the lawns which surround most urban and suburban homes. Short-mown grassland provides limited habitat value for most taxa (Norton et al., 2019). A growing body of knowledge demonstrates negative ecological and environmental effects of urban lawns (Watson et al., 2020). Perhaps most importantly, lawns are emblematic of humans’ broken relationship with the Earth (Tallamy, 2020). We have cultivated plants to meet our needs rather than the needs of nature as a whole.

This project will show the beauty and diversity of plants native to this part of Ontario, and the functionality of Green Infrastructure. Using interpretive signage and online and print educational materials, this project will become an important resource as we work to change our relationship with nature and restore the damage created by human activities. Over time, the landscape will be a source of cuttings and seeds that can be shared with the community. It could even be the genesis of a new native plant nursery – there is currently none in Haliburton County.

This document will describe how the project site fits into Ontario’s ecological zones and will show how local bylaws and policies can support or hinder naturalization. It will analyze the site as it currently exists and show how it will be modified to provide the basis for a successful naturalization project. Finally, it will describe the finalized site concept, demonstrate how the public will be engaged in its creation, and show how we plan to monitor and maintain the landscape over the long term.

Site Description

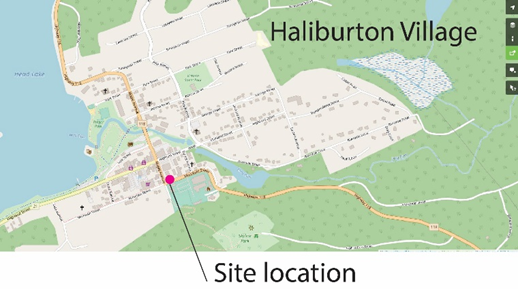

The project site is on the lot of Lucas House, in Haliburton Village. The lot is 40m x 24m and includes a 110-year-old, three floor building and large gravel parking lot. The site is in a prominent position, opposite the municipal office and next to the post office. Surrounding lots (mainly commercial zoned) are built on, with grass and/or gravel surrounding the buildings. As the town is small, less than half a kilometre from the site is continuous woodland and a river. Residential buildings are about 100 metres away.

The site sits within the following Ecological Land Classification (ELC) Framework.

Ecozone: Boreal Shield

Ecoprovince: Southern Boreal Shield

Ecoregion: Algonquin-Lake Nipissing

Ecodistrict: Algonquin (06.6.098.0413)

It should be noted, however, that the site is in an urban location, which due to its built nature makes it hard for any naturalization project to mirror non-urban Ecodistrict characteristics.

Policy and Program Review

The project site has Commercial zoning. There are two tiers of local government: the local municipality of Dysart et al, which is within Haliburton County. It is important to be aware of policies that support or do not support naturalization so that we can conform to bylaws and the long-term goals of our municipalities, and to make it easier to obtain financial and community support. While in this small, rural community I could find no program that directly supports naturalization, there are documents that support environmental protection and sustainability, although it should be noted bylaws with regard to property standards do not necessarily conform to current thinking on naturalization.

City Plans

The municipality of Dysart et al has an Official Plan which aims to guide the use of land in the municipality. It aims to assist decision making by public and private sectors. For the purposes of our project, it will help us make decisions in the context of consistent and predictable public policies. Elements of the plan of relevance to this project include:

- A statement on the importance of the natural environment. One of the plan’s objectives is “to promote a healthy and sustainable natural environment.” All new development and the redevelopment of existing properties “will be considered within the context of sound environmental planning.”

Haliburton County also has an Official Plan. Elements of the plan of relevance to this project include:

- A focus on the natural environment, which “forms the basis for Haliburton’s way of life and its stewardship is central to this Plan.”

- Under climate change, it states development considerations include the promotion of GI, which is included in this project.

Policy and Bylaw

Dysart et al has a Property Standards Bylaw, which stipulates the standards for the maintenance and occupancy of a property. Relevant to this project are the following:

- Yards should be free of “brush, undergrowth and noxious weeds as defined by the Weed Control Act.” This suggests the need to exclude invasive plants.

- It says that “lawns shall be kept trimmed and not be overgrown or in an unsightly condition out of character with the surrounding environment.” This bylaw could affect our plans if we choose a meadow-type naturalization. It should be noted that over summer 2022, we allowed the grass to grow at the project site, which resulted in vegetation reaching two feet high. There was no bylaw enforcement.

Functional plans and guiding documents

Dysart et al recently approved a new Strategic Plan. One of the plan’s key values is environmental stewardship, to “respect and protect our natural environment.” One of the plan’s strategic pillars is sustainable growth and development, “to promote and manage growth in a way that protects, respects and celebrates our natural landscape.” I would argue that an urban naturalization project is in line with this aim.

Programs

While I was unable to find programs that specifically addressed naturalization projects, Haliburton County does have documents that address climate change. Its Corporate Climate Change Action Plan includes the promotion of GI as well as the protection of natural assets and the enhancement of nature-based solutions. Both GI and other nature-based solutions will be used in this project.

One of the resources in Haliburton County’s Community Climate Change Action Guide is, “Reimagine your lawn to support biodiversity, reduce water and fertilizer use, and eliminate the noise and greenhouse has emissions associated with mowing.” This project’s design will avoid mown grass, although it should be noted this is in conflict with Dysart at al’s Property Standards Bylaw.

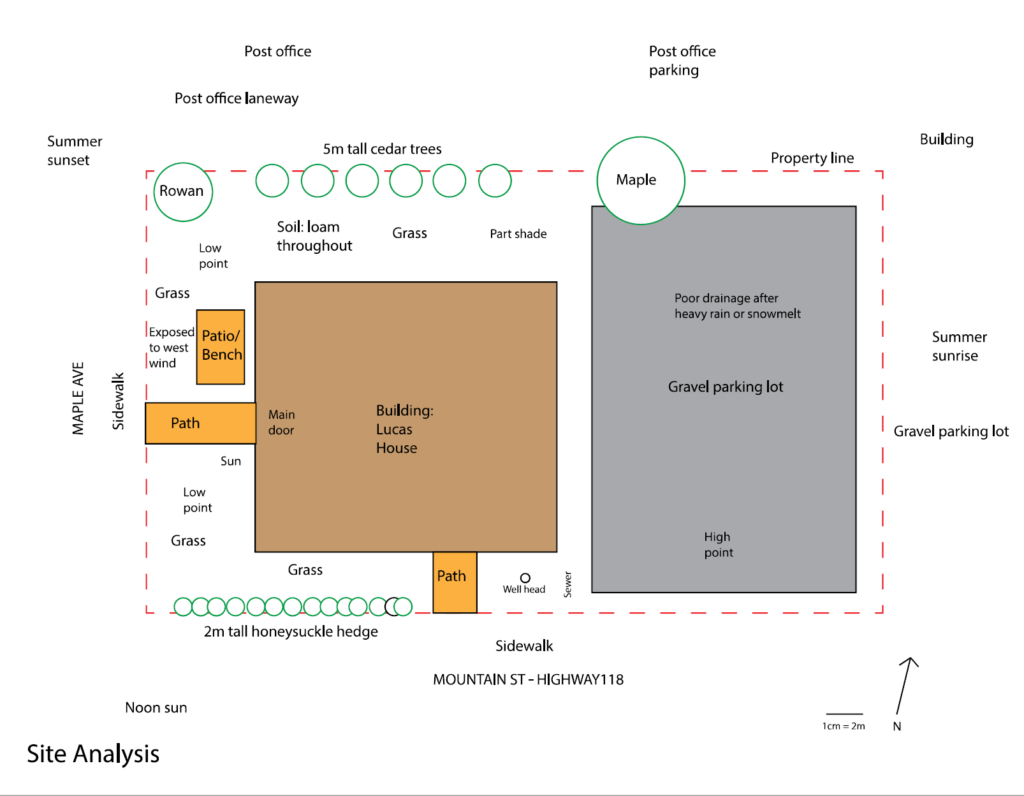

Site Analysis

The topography of the site is mainly flat, but there is a slight slope from Mountain Street to the back of the parking lot. The front of the building, facing Maple Avenue, faces west, and therefore receives a lot of sun. The south-facing part of the lot is partly shaded by a honeysuckle hedge. The northern part of the lot is partly shaded by the building, although receives some sun in the afternoon in summer. The parking lot is in full sun, except on winter afternoons, when it is partly shaded by the building.

Vegetation includes a honeysuckle hedge, one rowan tree, which is in good condition, a row of tall cedar trees, which are in excellent condition, and one sugar maple, which is in good condition. The lawn, which is on the north, south and west sides of the building, was allowed to grow long in the summer of 2022. The following plants were found in the lawn: Canada fleabane, goldenrod, fall aster, vetch, clover, wood sorrel, yarrow, oxeye daisy. The site is regularly grazed by white-tailed deer. Song sparrows, robins and pigeons are visitors.

The prominent location and structural features of the site make it an excellent candidate for a demonstration garden to promote naturalized landscape design. The greatest opportunity is to show how the use of native plants, in sun as well as part-shade, together with Green Infrastructure can provide aesthetic and functional benefits that can be mirrored by other commercial and residential properties. The parking lot is both a challenge and an opportunity: a challenge because of traffic circulation and the need to provide parking; an opportunity to show how green infrastructure can solve drainage problems. Shade on part of the site is also a potential challenge but can be mitigated by plant choice. Perhaps the greatest challenge will be public perception while the landscape is under construction and before it is fully established.

Site Modifications

The site is in a moderately degraded state, in the main because of the large, barren parking lot and because of the lawn. The site doesn’t need major modifications in order to implement the plan. However, the following modifications will be applied before the full site concept can be implemented: 1) re-grading of parking lot to facilitate the creation of a bioswale and pond; 2) removal of existing lawn to allow for native grass and perennial planting; 3) creation of planting beds along the perimeter of the parking lot, 4) addition of topsoil/re-grading to avoid pooling of water on lawn at western side of building.

The existing parking lot has drainage issues, particularly after heavy rain or after rapid snowmelt. Instead of installing Grey Infrastructure – concrete and plastic materials – the area will be re-graded and Low Impact Development (LID) installed in the form of Green Infrastructure: a bioswale along the north boundary of the parking lot leading to a small pond/wetland on a low point of the property will capture water runoff. These ecosystem services will have the benefit of solving the drainage issue while providing habitat and food for wildlife. The parking lot will be made sightly smaller after adding planting beds along its circumference for native shrubs and trees. Over time, trees will provide shade for the parking lot. The trees and shrubs will also provide food and shelter for wildlife.

The existing lawn will be removed to allow the planting of native grass and perennials. The soil is in good condition and does not need amendments. A honeysuckle hedge along the south side of the property will be hard pruned.

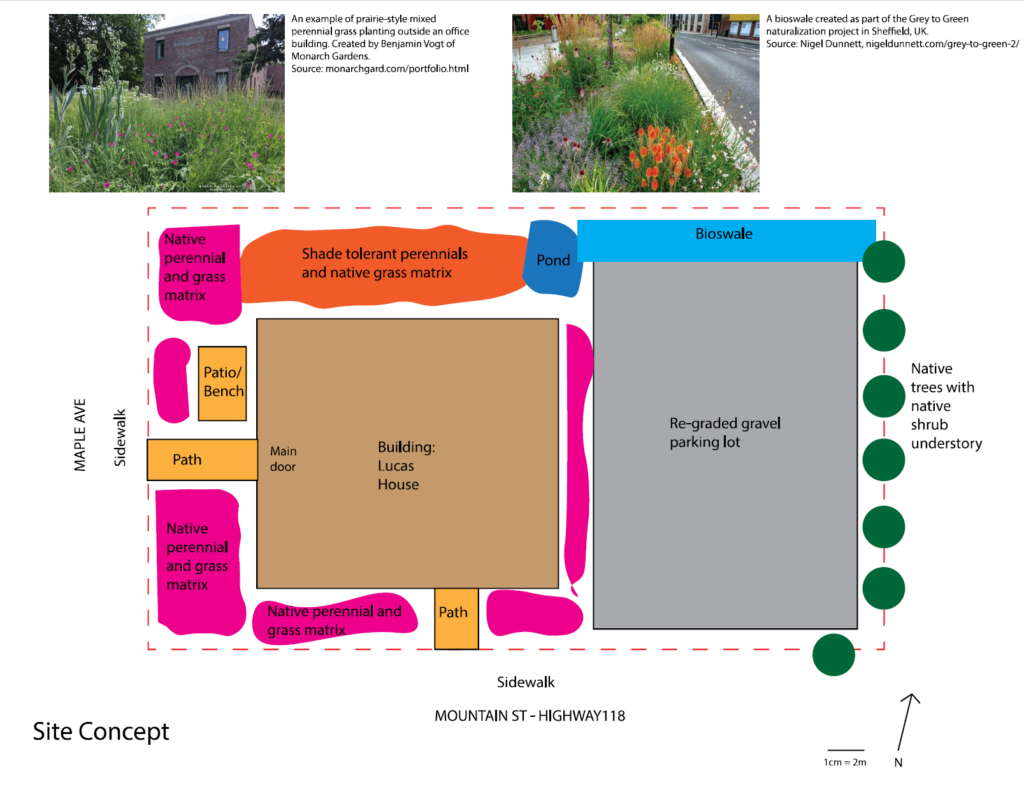

Site Concept

This project will create an aesthetically pleasing landscape which restores a functioning ecosystem to a corner of downtown Haliburton.

Replacing the lawn

The main and most obvious element will be a mixed perennial/grass planting on three sides of the building. This will increase the level of complexity within the landscape. With the lawn replaced, a matrix of native grass and native perennials will be sown and planted, with sun-loving species on the west and south-facing aspects and shade-loving species to the north. I plan to use a “green mulch” of native grass to supress weeds. Plants will be chosen for varied heights and blooming times, with taller plants away from the sidewalks. They will be planted in drifts, with grass between main plantings. Shorter plants will establish near the bench at the front of the building. The improved view from office windows will increase the quality of life for employees – studies, such as those by Gaekwad et al. (2022), found that natural environments had an effect on increasing positive emotion and decreasing negative emotion. By choosing native plants, we will be able to re-establish a functioning ecosystem, attracting a wide variety of insects, birds and mammals. According to Dark and Tallamy (2014), a native is “a plant that has evolved in a given place over a period of time sufficient to develop complex and essential relationships with the physical environment and other organisms in a given ecological community.”

Plants will depend on availability but will likely include some of the following. Sun, part sun: black-eyed Susan, foxglove beardtongue, hairy beardtongue, New England aster, Virginia mountain mint, wild bergamot, hoary vervain, slender vervain, harebell, wild chives, wild strawberry, butterfly milkweed, wild columbine, flat-topped aster, New England aster, clammy ground cherry. Shade: white trillium, bloodroot, ferns, bunchberry, bearberry, zig-zag goldenrod, blue violet, white snakeroot, wild geranium, wintergreen, bottle brush grass. Grasses: Indian grass, little bluestem, big bluestem, side oats gramma, and Canada wild rye.

The re-graded parking lot will have a bioswale at the northern end. This will be planted with several layers of plant material, and will slope towards the west, leading into a wildlife pond.

Finally, native trees and shrubs will be planted along the perimeter of the parking lot. These trees might need protective barriers during their establishment phase due to the large number of white-tailed deer in the area. The trees and understory will provide habitat and food for wildlife throughout the year, as well as providing shade for the parking lot. We aim to include trees that provide fruit for human consumption, with the aim of showing that a naturalized landscape provides sustenance for all nature, including Homo Sapiens. Trees and shrubs will include some of the following: red oak, black walnut, staghorn sumac, yellow birch, grey dogwood, redosier dogwood.

5-ways-to-reduce-mowing/

Cues of care will be used throughout the landscape. For example, a strip of grass will be mowed along the western perimeter and planting will be in drifts rather than a random matrix. A mown path will be installed along the northern position of the site, connecting the sidewalk to the parking lot.

In summary, the concept for this landscape is designed to inspire and to educate. It will inspire because it will open people’s minds to the availability of native plants and the use of Green Infrastructure. It will educate by showing how to create such a garden, the species to use, and how Green Infrastructure works.

Project engagement

As this project is on private land and I am the designer and client, there are few stakeholders who need to be directly involved. However, as this site is in a prominent position in town and because the aim is to educate residents and visitors, we will be developing many informational materials. This is particularly important during the establishment phase of the project, and also during the fall season, when seed heads will be allowed to stay – something some residents may consider messy due to the established cultural lens that expects lawns to be mown and kept neat.

Higher levels of education are the most consistent predictors for concern about the environment, suggesting that educational campaigns, interpretive signage, and public discourse lead to greater neighbourhood-level adoption of native plant gardens (Kiers et al., 2022). Kiers et al. suggest that residential landscape designs and management practices are an example of social contagion and that residents are directly influenced by the shape, colour and location of their neighbours’ gardens.

interpretive-trailhead-signage

I will be developing illustrated interpretive signage that will be placed on the west and south sides of the site to inform people of the project and about the benefits of a naturalized landscape.

Printed material will be available, educating people about the project. This material will include a plant list, allowing people to replicate the vegetation choice at home.

A website will be created chronicling the development of the project over the months, along with further information about the benefits of a naturalized garden. This will be coupled with social media postings.

I aim to secure an interview with our local community radio station and with the local newspaper. I also hope to partner with local organizations that can provide support and networking opportunities. These include the Haliburton County Master Gardeners, Environment Haliburton!, and the Haliburton Highlands Land Trust. I will also explore partnerships with local schools to see if the site is suitable for any nature-based curriculum they have.

Project Implementation and Monitoring

The project will be managed by myself and implemented by myself and outside contractors. A landscaping contractor will be used to re-grade the parking lot, dig the bioswale and pond, and create planting beds around the parking lot perimeter. I will remove the grass lawn myself and will work with Grow Wild Native Plant Nursery in Omemee, ON, with plant sourcing, and perhaps with final plant placement.

I have applied for a grant from the federal government that, if approved, will pay for 50% of the costs of this project. The estimated budget is $20,000.

Maintenance will be important. While a naturalized landscape over the long term needs less maintenance and human inputs such as fertilizers and weed killers than traditional gardens due to choosing plants that are suited for the area (Chu et al., 2022), it will still require monitoring and maintenance, particularly in the establishment phase.

During the establishment phase, the site will be monitored to make sure plants are well placed and are establishing themselves. Weeds will be removed, with particular care taken to monitor for invasive, non-native plants, which are a major cause of global biodiversity loss (Glen at al., 2013).

Over the long term, maintenance will be required, at a schedule of approximately one day per week, to keep the landscape aesthetically pleasing and to make sure it continues as a functioning eco-system. Non-native invasive plants will be removed and plants that are not thriving will be relocated. The bioswale and pond will need to be managed to make sure they continue to function properly. Regular spring maintenance will be carried out to remove seed heads and dead plant material. I recognize, however, that a naturalized garden should to some extent show me, as the creator, how it wants to develop, if I allow natural processes to take place. This will likely change the character over time of what is, in its essence, a living project.

The project will also be monitored to see if was effective in meeting its goals, particularly if biodiversity has increased and if the Green Infrastructure is fulfilling its role. Water-flow patterns and plant establishment will be monitored. Over the long term, organic accumulation will be assessed. A photographic inventory will be created, which will be shared on the project’s website. The educational materials will be maintained and developed to keep them accurate and in good shape.

Periods of project reflection will be established to determine what worked well and what needs improvement for any future projects.

Conclusion

This project will be implemented during 2023. I was able to spend a lot of time analyzing the site to understand its opportunities and constraints. I performed extensive research into bylaws, financial assistance programs, and how to create a functioning ecosystem on a partly degraded location. Most importantly, I was able to create an exciting vision for the future of this site that I hope will inspire members of the community to change the way they look at their own landscapes and begin to understand that we have a duty to respect nature.

References

Chu, Z., Guan, Y., Ma, J., & Yuan, Y. (2022). The Ways to Improve the Ecological Benefits of Carbon Sequestration of Garden Green Space. E3S Web of Conferences, 350, 1027–. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202235001027

Darke, R., Tallamy, D. (2014). The Living Landscape: Designing for Beauty and Biodiversity in the Home Garden (Illustrated Edition). Timber Press.

Dysart et al (2016). Dysart et al Economic Development Strategy. https://www.dysartetal.ca/en/municipal-government/Economic-Development-Strategy-052316.pdf

Dysart et al (no date available). Dysart et al Haliburton Village Built Form Guidelines. https://www.dysartetal.ca/en/build-and-invest/Planning%20Resources/Haliburton%20Village%20Built%20Form%20Guidelines.pdf’

Dysart et al (2017). Dysart et al Official Plan. https://www.dysartetal.ca/en/build-and-invest/Planning%20Resources/Dysart%20Official%20Plan.pdf

Dysart et al (2014). Dysart et al Property Standards Bylaw. https://www.dysartetal.ca/en/municipal-government/By-Law%20Enforcement/By-Law%202014-29-Property-Standards-By-law.pdf

Dysart et al (2022). Dysart et al Strategic Plan. https://www.dysartetal.ca/en/municipal-government/resources/Dysart%20et%20al%20-%20Strategic%20Plan.pdf

Dysart et al (2021). Dysart et al Zoning By-law Maps. Schedule A, Map 1 – Haliburton. https://www.dysartetal.ca/en/build-and-invest/Zoning%20Maps%20Update/Sch%20A-Map%201-Haliburton-350.pdf

Glen, A. S., Pech, R. P., & Byrom, A. E. (2013). Connectivity and invasive species management: towards an integrated landscape approach. Biological Invasions, 15(10), 2127–2138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-013-0439-6

Haliburton County (no date available). Haliburton County Community Climate Change Action Guide. https://www.haliburtoncounty.ca/en/planning-and-maps/community-climate-action-guide.aspx

Haliburton County (2021). Haliburton County Corporate Climate Change Action Plan. https://www.haliburtoncounty.ca/en/planning-and-maps/resources/Documents/Draft-Corporate-Adaptation-Plan.pdf

Haliburton County (2017). Haliburton County Official Plan. https://www.haliburtoncounty.ca/en/planning-and-maps/resources/Documents/County-of-Haliburton-Official-Plan-2017.pdf

Kiers, A., Krimmel, B., Larsen-Bircher, C., Hayes, K., Zemenick, A., & Michaels, J. (2022). Different Jargon, Same Goals: Collaborations between Landscape Architects and Ecologists to Maximize Biodiversity in Urban Lawn Conversions. Land (Basel), 11(10), 1665–. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11101665

McGill, B. J., Dornelas, M., Gotelli, N. J., & Magurran, A. E. (2015). Fifteen forms of biodiversity trend in the Anthropocene. Trends in Ecology & Evolution (Amsterdam), 30(2), 104–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.11.006

Meineke, E. K., Davies, T. J., Daru, B. H., & Davis, C. C. (2019). Biological collections for understanding biodiversity in the Anthropocene. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences, 374(1763), 20170386–. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0386

Norton, B. A., Bending, G. D., Clark, R., Corstanje, R., Dunnett, N., Evans, K. L., Grafius, D. R., Gravestock, E., Grice, S. M., Harris, J. A., Hilton, S., Hoyle, H., Lim, E., Mercer, T. G., Pawlett, M., Pescott, O. L., Richards, J. P., Southon, G. E., & Warren, P. H. (2019). Urban meadows as an alternative to short mown grassland: effects of composition and height on biodiversity. Ecological Applications, 29(6), 1095–1115. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1946

Statistics Canada (2017). Ecological Land Classification (ELC). https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3VD.pl?Function=getVD&TVD=426171&CVD=426173&CPV=06.6&CST=20112017&CLV=2&MLV=4

Tallamy, D. (2020). Nature’s Best Hope (Illustrated Edition). Timber Press.

Vogt, B. (2017). New Garden Ethic: Cultivating Defiant Compassion for an Uncertain Future. New Society Publishers.

Watson, C. J., Carignan‐Guillemette, L., Turcotte, C., Maire, V., Proulx, R., & Ming Lee, T. (2020). Ecological and economic benefits of low‐intensity urban lawn management. The Journal of Applied Ecology, 57(2), 436–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13542